The proposal to turn Medicaid funding into no-strings-attached block grants to states will be used to shore up state budgets, not provide healthcare. No wonder some politicians in Kansas and Missouri love it.

Linked by a common border, the Oregon Trail, the California Trail, the Pony Express Route, Highway 36, Highway 40, Highway 24, Highway 56, Highway 59, Highway 169, I-70, I-35, and I-435, Missouri is closer to no other state than Kansas.

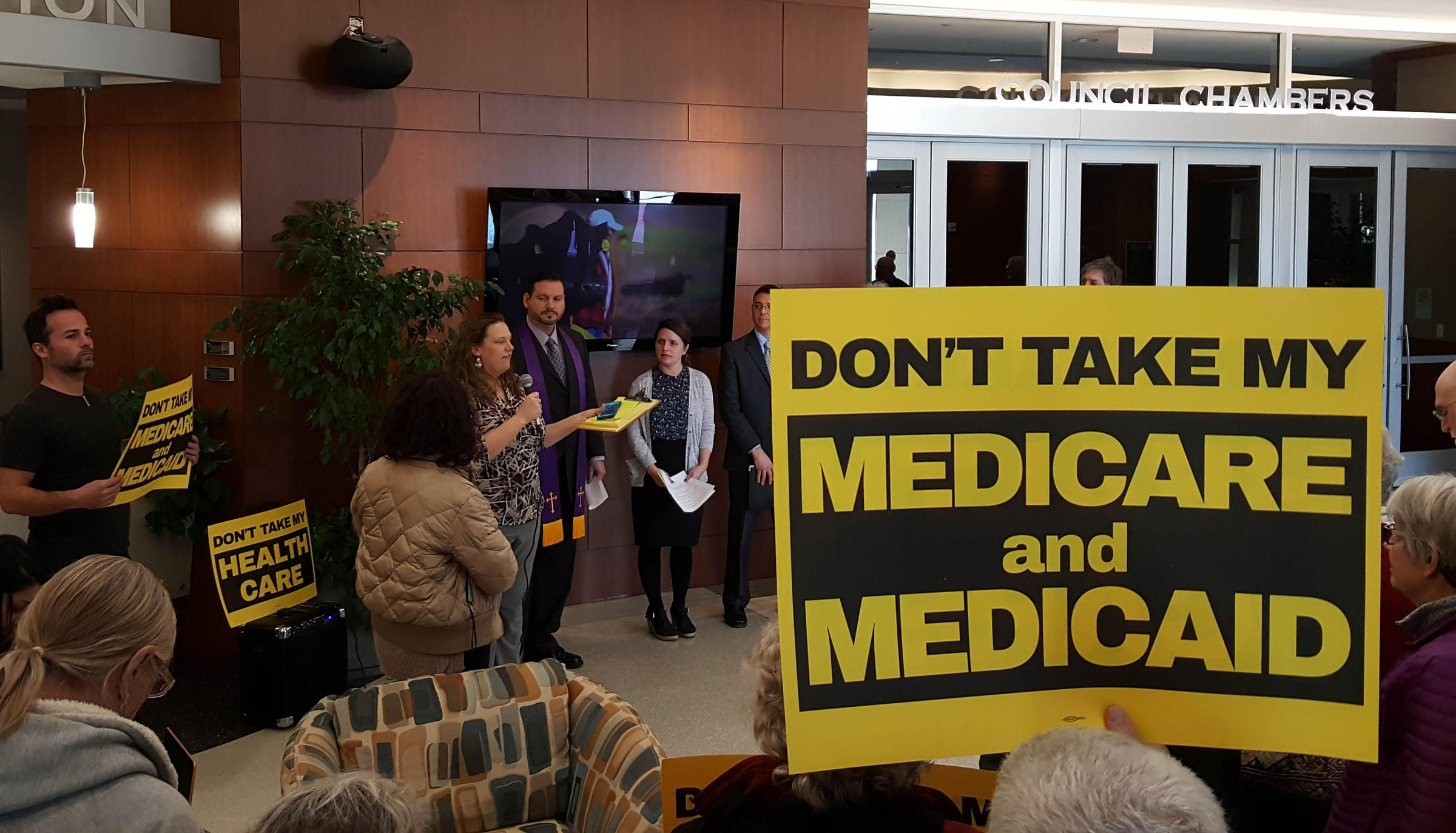

During the Civil War, we were enemies, burning each other’s cities. Now we’re in another war, only this time Kansas and Missouri are allies in the war on Medicaid.

Kansas is struggling to offset tax credits and falling revenue with cuts to state expenditures. Governor Sam Brownback is looking for another $300 million to replace what has become continuous annual revenue dips. It’s much the same with Missouri, where newly elected Governor Eric Greitens will double cuts suggested by his predecessor, Jay Nixon, to something close to what Kansas will do. And the Kansas legislature approved a Medicaid funding increase that Brownback vetoed. Word on the street is that votes for an override are close to enough. On top of that, courts have ordered Kansas to come up with a plan to adequately fund education. One state Senator has offered a bill that increases an earlier proposal of $75 million by a factor of ten to $750 million over ten years.

Newsflash: Governor Brownback has been nominated by the Trump Administration to be our Ambassador to Italy. Sorry Italy, but if he is confirmed then Kansas legislators would be free from Brownback’s vetoes, which might allow their budget to grow.

While Missouri’s overall approach to budgeting and tax credits becomes ever more like Kansas’, Governor Greitens has appointed a conservative state tax reform committee whose first move might be to eliminate tax credits, like one used widely across the state to fund renovation of historic buildings. That poses a threat to at least one big project, improvements to landmark Kemper Arena in the increasingly popular convention destination, Kansas City.

Though fuel taxes in both states are among the lowest in America, rather than increase those taxes, Missouri and Kansas have wrangled with road funding shortfalls, looking at solutions like turning public highways into privatized toll roads. I suppose state leaders believe tax payers won’t mind the double dipping into their pockets such a move would represent–taxation plus fees. That’s because all the money taxpayers have paid to build and maintain highways and bridges would be forfeit–along with existing tax levies–in exchange for user fees up front paid to corporations that would manage and care for highways.

Now, with the Trump administration, it looks as though Medicaid block grants might be the latest double-dip tax extender for budget busting, and the answer to a Missouri-Kansas prayer.

But not for those who rely on Medicaid. That’s because states determine how those funds will be spent.

Rural as we are, with real healthcare challenges, neither Missouri nor Kansas accepted stepped up federal Medicaid aid to help stiffen Obamacare mandates. That hurt state Medicaid patients right off the bat, when the Affordable Care Act began.

More than one fifth of all Americans are enrolled in Medicaid. But Kansas and Missouri rely on Medicaid treatment for one third of ALL their children. It is estimated that 7% of children in both states who are NOT enrolled in Medicaid are actually eligible. If those children were included today, 40% would be covered under the federally directed plan.

What’s more, 25% more of the rural population relies on Medicare than those living in urban settings. It might be higher except for states like Kansas and Missouri, and funding restrictions they have imposed by refusing to answer needs of their citizens.

Average annual cost of treating children under Medicaid runs less than $3,000 per child per year while adults whose health needs were ignored as children cost the system more than $8,000. The result has been that medical help for children and the poor, located mostly in rural areas of both states, falls short of the mark with regular cuts to services a rule rather than exception. Now, both states say they might accept federal Medicaid aid they once declined with one difference; this time Medicaid block grants, their preference, might not necessarily be required to deliver healthcare to the needy.

Free money!

In other words, states would be free to siphon off no-strings-attached federal Medicaid funding. However, at least one study has shown that relying on block grants results in a steady decline of adequate Medicaid funding. So not only could states use the money free of federal guidelines, but over a period of years, costs would exceed funding at a greater pace.

That’s bad news for Medicaid recipients as health care costs keep growing.

Kansas’ $3.4 billion dollar privately managed KanCare Medicaid program has had a falling out with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which has denied an extension to KanCare due to what they said was a lack of control over the program. (that’s because three private companies were in control). Most recently that has resulted in loss of dental care services for about 350 nursing home residents of the state who are dependent on Medicaid for their healthcare, and a dental provider in Oklahoma who declined to provide service until funds are available.

Kansas has caused much of its own budget problems through an unbridled approach to granting tax credits and exemptions. Missouri hasn’t quite gone as far–yet. But one Missouri lawmaker has proposed a unique tax exemption for political contributions. It’s difficult to see how making political contributions tax deductible could help build roads and bridges and fund healthcare for the poor. But it would certainly plump up some already very fat cats.

That’s just another example of how politically expeditious government in both states has become.

That brings to mind a rural physician in West Virginia who commented that a poll of his patients showed most of them opposed to Obamacare while the same patients extolled the virtues of the Affordable Care Act.

ACA and Medicaid are one thing. Medicare is something else. And turning to block grant funding for Medicaid could eventually spread to Medicare with things like privatization, payment caps, and other proposed overhauls to the nation’s premier retirement program providing for the needs of almost 54 million citizens.

With only 19% of the total population, 24% of RURAL Americans are dependent on Medicare. Chances are if Medicare were to be privatized, or even modified, the first to suffer would be Americans in out of the way places like Kansas and Missouri, and all rural communities no matter what state they’re in.

If that happens, who do we turn to next?

Richard Oswald is a fifth-generation farmer and president of the Missouri Farmers Union.